It’s not easy being weird but I’ve spent the course of some five years researching and drafting what has so far resulted in an 8,000 word essay I wound up calling Revolt Club, Long Island City: Uncovering a Lost History of Queens Political Clubs. I started out by wanting to make the slightest point.

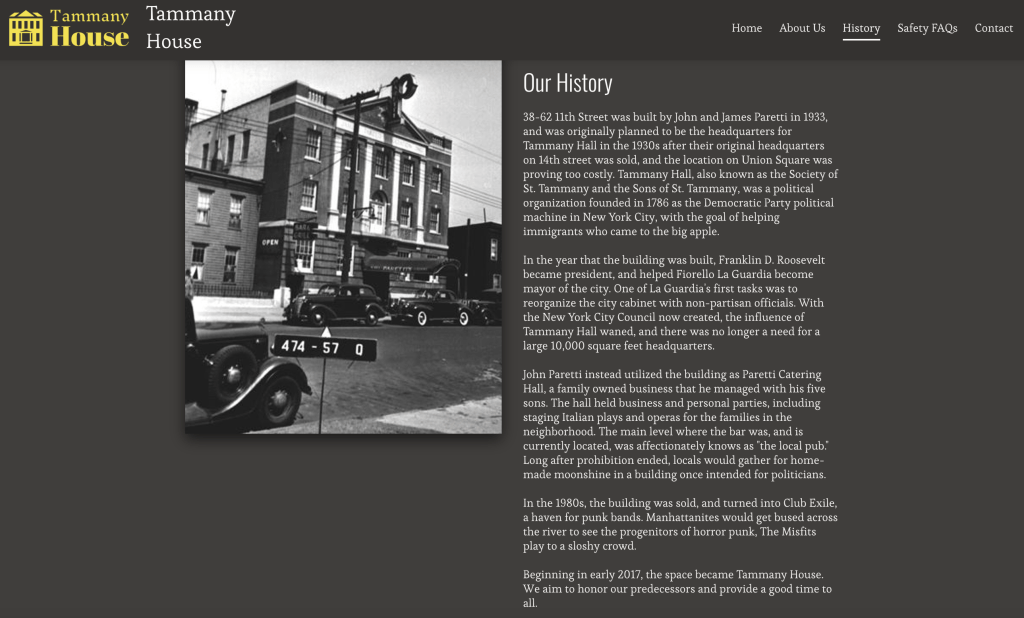

Around 2019/2020, I set out to correct rumors around a building at 38-62 11th Street, a three story, brick Colonial on an industrial street. If you’ve ever lived in or around Queensbridge, the Ravenswood Houses or in the mixed-use area in between (or just wandered around north of the Queensborough Bridge), there’s likely a decent chance you’ve noticed a vertical EXILE marquee attached to an imposing, stately facade with 13 front windows (plus a transom window and five front basement windows), wide, black doors and various ornamentation. Less obvious would be the two-story ballroom inside on the second floor with a surrounding balcony, the site of all-night Depression era dances and 1980 punk shows that included the Misfits. The site is not an official landmark but it’s arguably among the most intriguing and exquisite prewar gems in the Long Island City-Astoria area, up there with the Long Island City Courthouse, MoMA PS1, the Terra Cotta Works building, the Sohmer Piano Factory, the Loew’s Triboro Theater, the Masonic Temple and the Moose Lodge, and it tells a story about the neighborhood and about modern Queens.

When I moved to 36th Avenue in 2015, I was curious about the building, with the inscription James J. Paretti Association, Inc., across the top and 1933 at the bottom corner. I figured the building once housed some kind organization that served an Italian community that once existed more prominently in Long Island City, but I had no idea what sort of organization, and how it possibly served the community. It wasn’t like I could find a Wikipedia page about James J. Paretti, or any kind of reliable article anywhere on the immediate surface of the Internet. One blog post, an advertisement for an event called Beautiful and Damned, made claims about the building, ostensibly to lure a Brooklyn and Manhattan crowd to the first Queens stop on the F train, and into a desolate, industrial area at night for a 1920s-themed party. The promotional content claimed that Tammany (the former name for Manhattan’s Democratic Party organization) built the Paretti building as a headquarters. (Sure, the building looked like Tammany Hall itself at Union Square but smaller). The playful advertisement also claimed the building became a speakeasy, and only later became a “Democratic party headquarters” before one day transforming into a punk rock club. For a while, this was the only thing you could find online about Paretti Hall, unless you used newspapers.com or the New York Times “Time Machine” tool or some other site (likely by a paid subscription or a library account) that let you explore archived newspapers–but even that would be limited to a handful of articles referencing James Paretti or the clubhouse.

I read the Beautiful and Damned advertisement/flyer website, probably in 2015 (and watched its silent-film styled video), and over the years, when I thought of writing my own, journalistic blog post, I Googled the site again, and found that in 2017, a company called Warehouse LLC, which purchased the site in 2014, began to market the building as an event space called Tammany House. Tammany House posted pictures of one or more events, a photo shoot, a concert, that happened in the then-renovated interior. Another company, Motif Studios, also rented the space as Triplex LIC. Both companies’ websites echoed the rumor that Tammany built Paretti Hall!

Tammany House invented its own elaboration on the so-called history, claiming that John and James Paretti built the site in 1933 but that it was “originally planned to be the headquarters for Tammany Hall after their original headquarters on 14th Street was sold.” The Tammany House website went on to say that in the year the building was built (1933), Franklin D. Roosevelt became president (that’s true) and “helped” Fiorello LaGuardia become mayor. Well, I don’t know to what end that might be true (FDR was a Democrat, LaGuardia was a Republican who ran on a Fusion ticket) but anyway LaGuardia did win an election in 1933, and became mayor in 1934. The Tammany House website says LaGuardia reformed City Hall (which is true), and then, “With the New York City Council now created,”(the City Council did not go into effect until 1938) “the influence of Tammany Hall waned” (that’s true) and there was no more need for a “10,000 square feet” Tammany headquarters in Queens. The website then concluded that James Paretti decided to use the building as a catering hall.

In 2017 a local Long Island City blog called LIC Talk helped promote Tammany House with a blog post called The Legend of Paretti Hall. The author made the lazy remark: “Who exactly was James J. Paretti and what was his ‘Association’ are lost to the sands of time. In fact the building’s precise history is not fully verifiable. ”

You might say that I took that as a personal challenge. I thought to myself: there has to be a way to answer those questions! First, I lucked out, because in 2018 two of James Paretti’s descendants posted comments on LIC Talk‘s post, and one left an email address. That got me talking to the family (by sometime in 2019 or so), which was amazing, and I was grateful. They connected me to some other people from the neighborhood. Then, around summer 2020, I started digging into Census records and digital newspaper archives. Later, starting in 2021, I spent most of my weekends for a few years in the archives of the Queens Public Library’s Central branch in Jamaica, reading primarily the Long Island Daily Star, which had never been digitized but had a lot of details on James Paretti. First I read all of 1935, when James Paretti ran for alderman, then I focused mainly on election seasons from roughly 1925 to 1938. When not in the library I simply educated myself on New York City history, and let me tell you Queens history from 1898 to 1945 as far as I can tell barely exists in the form of any books or serious literature.

Here are three points why the Tammany House claims are false and you might even say problematic.

- Tammany Hall was a Manhattan organization. There was no possibility of it ever setting up a headquarters in Queens. Queens had its own Democratic party organization. Sure, Tammany’s Al Smith was governor of the whole state in the 1920s, but the organization itself represented one manifestation of the New York County Democratic Committee, and it would not in all likelihood relocate its headquarters to some other county. That would in essence be absurd. In fact the early Queens Democratic County Committee was not an ally of Tammany. And in the 1930s when James Sheridan, a New Dealer, took over the Queens Democratic Party, it was if anything more related to the Bronx Democratic Party than Tammany.

- James J. Paretti had essentially nothing to do with Tammany Hall. The closest link I can make is that in 1929 he ran for state assembly with the Clean Government Party (by then calling itself the Queens Democracy), which was led by Frank X. Sullivan, who lived in Queens but had run a Tammany campaign for Jimmy Walker in Queens in 1925. (There were for a few years or so “Queens Tammany” clubs in the Sullivan faction.) The building resembles Tammany Hall, but likely just as a figurative Italian version of a Tammany Hall for the Long Island City area. Labeling the building “Tammany House” in a roundabout way erases the actual history of Italians in politics in Long Island City and Astoria during the turbulent 1930s. Besides running a club that served as a resource for the community (call it “machine politics”, if you will), Paretti served in the Board of Alderman for two years–an incredible two years that involved major New Deal works projects in his district, which spanned LIC and Astoria. Not only that, but in 1935 he defeated an incumbent, Carl Deutschmann, for alderman, becoming, with Mario Cariello, I believe one of the first two Italian-Americans to represent the area in government. We might take for granted now that Italians are normally in office in New York, but these were first-generation children of immigrants, when the community was still relatively new to the country and considered poor and outside of the system, Fiorello LaGuardia notwithstanding. Imagine if in 90 years someone came across the names Julie Won, Linda Lee, Shekar Krishnan, Steven Raga or Jenifer Rajkumar and said they ran a catering hall, or something? And what if there were a landmark, or some type of time capsule, for any one of them, and someone gave it a made-up, irrelevant history?

- The Paretti building was, indeed, used as a catering hall, but that was secondary to its purpose as a political club. You can say the underlying purpose of the club was to elevate the Italian community into power in Queens’ First Assembly District, and to supplant the powerful Regular Democratic Club of the First A.D., which became associated with the corruption of the boss John Theofel in the early 1930s. Tammany House likely got its details about the place staging Italian operas from a self-published memoir called Rita, but the author, Mary Restivo, was recalling her early childhood, and wouldn’t necessarily remember the political story of James Paretti. The Paretti Club had other locations, including the family residence next-door, before building the large, extravagant clubhouse, which you might say was a statement. There were at the time hundreds of political clubs in Queens, some which met in stand-alone clubhouses, others in storefronts or residences. These clubs also hosted rallies and dances in the old social halls, such as the Moose Lodge or the ballroom which is now Break Bar. In the high point of political clubs, Queens was believed to have more political clubs and civic associations than the other four boroughs, despite being second-to-last in population. That said, the Paretti building is actually a testament to the cultural history of Queens in the first half of 20th Century.

I’m not saying that I ever considered my investigation finished. It isn’t, but eventually I felt ready to publish a sort of origin story that I was able to piece together. It’s the story of a revolt club. Maybe you’ll want to set aside some time to read it, and I’d be grateful. Or just wait for me to write the more detailed story.